User Experience Design for Library Websites: Creating User-Friendly Digital Spaces

In an era where digital access to information has become paramount, library websites serve as critical gateways to knowledge resources, services, and community engagement. Academic and public libraries alike face the challenge of designing digital experiences that serve diverse user populations with varying  needs, abilities, and technological proficiencies. User experience (UX) design has emerged as an essential discipline within librarianship, offering methodologies and principles that center on users in website design and development.

needs, abilities, and technological proficiencies. User experience (UX) design has emerged as an essential discipline within librarianship, offering methodologies and principles that center on users in website design and development.

The Foundation of Library UX Design

At its core, user experience design in libraries represents a fundamental shift in how library services are conceived and delivered. As Andy Priestner, a leading voice in library UX, defines it, UX methods ensure that the user is at the center of what libraries do, moving away from staff agendas, convenience, assumptions, or gut feelings toward what users really need and really do (3). This philosophy aligns naturally with libraries’ historical mission of public service and user advocacy, making UX principles particularly well-suited to the library context.

voice in library UX, defines it, UX methods ensure that the user is at the center of what libraries do, moving away from staff agendas, convenience, assumptions, or gut feelings toward what users really need and really do (3). This philosophy aligns naturally with libraries’ historical mission of public service and user advocacy, making UX principles particularly well-suited to the library context.

The user-centered design (UCD) methodology has become the dominant framework for library website development. UCD emphasizes that the system’s purpose is to serve users, and that user needs should dominate interface design (4). This approach originated from Donald Norman’s work on cognitive engineering and has been widely adopted across library systems. Research demonstrates that libraries implementing UCD methodologies through triangulation—combining user surveys, interviews, and website analysis—gain a multidimensional understanding of their users that directly informs design decisions (4).

Understanding Library Website Users

Library websites must serve remarkably diverse user populations. Academic library websites, for instance, need to support students, faculty, staff, administrators, and alums, each with distinct intellectual pursuits related to research, teaching, and learning (13). This complexity extends beyond role-based differences to encompass variations in technological literacy, accessibility needs, and information-seeking behaviors.

Recent studies reveal essential insights about user perceptions and needs. Research on the Queens College Library website found that while the majority of users appreciated the content and considered it valuable for teaching and research, they also thought the website design appeared dated and that some content was inconsistent (4). Access emerged as a significant theme, underscoring the critical importance of ensuring that users can reach and use the resources libraries provide. These findings underscore a crucial principle articulated by Schmidt and Etches: library websites are for library users, not librarians (4).

Principles of Library UX Design

Schmidt and Etches have identified eight core principles that guide effective library UX design (5). These principles provide a framework for libraries of all sizes

to evaluate and improve their digital presence. The touchpoints they identify extend far beyond the website itself to encompass email communications, furniture, parking facilities, events, and newsletters—recognizing that user experience is holistic and spans both physical and digital environments (5).

The UX process in libraries follows a cyclical pattern: seek to understand users through ethnographic techniques, analyze and process the insights gained, and then design improved services or products based on those insights (3). Many libraries employ rapid prototyping models to implement improvements quickly, observe results, and iterate as needed. This agile approach allows libraries to respond dynamically to user needs without waiting for perfect solutions.

Accessibility

Accessibility has become increasingly central to library website UX design, driven by both ethical commitments and legal requirements. The 2024 update to Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act addresses web content accessibility for state and local government entities, including public libraries, schools, and universities (16). Under these regulations, libraries must comply with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 Level AA for all online services and electronic documents.

Research indicates that library website inaccessibility is fundamentally a problem of diversity rather than merely a technical issue (11). Inclusive information architecture must go beyond basic accessibility compliance to ensure usability for all user groups. This includes implementing features such as keyboard navigation, alternative text for images, captioned videos, explicit structured content, and sufficient color contrast (12). Studies emphasize that accessible design benefits not only users with disabilities but also enhances the overall user experience for all patrons.

architecture must go beyond basic accessibility compliance to ensure usability for all user groups. This includes implementing features such as keyboard navigation, alternative text for images, captioned videos, explicit structured content, and sufficient color contrast (12). Studies emphasize that accessible design benefits not only users with disabilities but also enhances the overall user experience for all patrons.

Libraries are increasingly prioritizing responsive design principles to ensure websites function across various devices and screen sizes, accommodating users with different abilities and preferences (12). However, challenges persist. Many library accessibility webpages themselves fail to meet user needs, often providing limited and straightforward information rather than comprehensive guidance on physical accessibility, services, and materials (20).

Information Architecture and Navigation

The organizational structure of library websites fundamentally impacts their usability and accessibility. Information that isn’t organized systematically becomes difficult for students or patrons to navigate, directly affecting the user experience and increasing the effort required to find information (14). Poor organization ![]() also creates maintenance challenges for library staff.

also creates maintenance challenges for library staff.

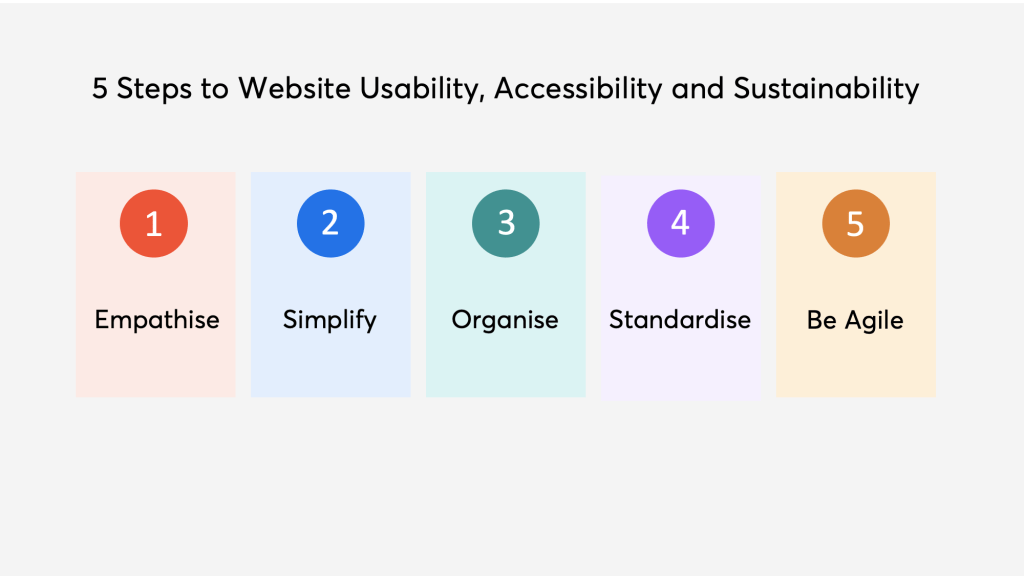

Recent research emphasizes a five-step iterative process for improving library website organization: empathize, simplify, organize, standardize, and be agile (14). This process begins with understanding users—their goals, accessibility needs, and search behaviors—and extends to understanding staff capabilities and constraints. Reducing duplicate content simplifies websites, potentially reducing the time users spend finding information while improving their perception of both the website and their own information-finding abilities (14).

Heuristic evaluation frameworks have emerged as practical tools for assessing information architecture in academic library websites. These frameworks typically divide websites into dialogue elements and apply integrated usability principles to identify opportunities for improvement (15). Task-based usability testing, while valuable, may prove inadequate as a sole assessment method because it doesn’t rely on broad enough dimensions to fully gauge user experience (1).

testing, while valuable, may prove inadequate as a sole assessment method because it doesn’t rely on broad enough dimensions to fully gauge user experience (1).

Designing for Access

A significant portion of modern library website UX focuses on facilitating access to digital resources, including online catalogs, e-book repositories, and research databases. UX design ensures that these platforms remain intuitive and meet user needs through features such as advanced search capabilities, reading recommendations, and personalized dashboards (6).

Research on e-book platform usability demonstrates how comparative testing can identify strengths and weaknesses of different systems. Studies employing task-based usability testing with think-aloud protocols have shown that students prefer specific aggregator platforms to publisher platforms, with usability tests revealing particular features that affect user satisfaction (1). These findings help libraries make informed decisions about which platforms to license and how to optimize user access.

Library management systems present unique UX challenges, as they balance the differing needs of students, faculty, librarians, and researchers (7). The design process for these systems increasingly incorporates qualitative user studies, complex persona development, and user journey mapping to track users’ mindsets and emotions throughout workflows, identifying both smooth-sailing points and frustration points (7).

Ethnography and Research

Contemporary library UX practice draws heavily on ethnographic research techniques to understand user activities and needs. Methods include semi-structured interviews, cognitive mapping, and observational studies (3). The library environment itself serves as a natural usability laboratory, allowing creative

https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/ux-ethnography-and-possibilities-for-libraries-museums-and-archives

research approaches. UX practitioners have conducted on-the-spot testing by approaching library users with brief evaluations, setting up feedback booths for candid input, and performing wayfinding tests with redesigned signage in actual library spaces (8).

This emphasis on direct user engagement reflects the recognition that library user tasks typically span both physical and digital touchpoints. Even simple activities can involve multiple channels and interfaces (8). Effective UX design must account for this complexity by considering how users navigate between different systems and spaces in their library interactions.

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite growing awareness of UX principles, many libraries face significant challenges in implementation. Resource constraints, including limited staff time and expertise, affect the scope of possible UX initiatives. Privacy concerns also shape UX practice in libraries differently than in commercial contexts. Since libraries take privacy seriously, designers may lack access to the breadth of behavioral data available in for-profit environments, as many libraries avoid using tracking cookies or storing individualized borrowing data (8).

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated changes in library website UX, as institutions rapidly moved services online and websites became the primary point of access for students and faculty (13). Libraries had to quickly update their websites to include information on remote access, coronavirus protocols, and daily operational changes. This crisis highlighted both the importance of flexible, user-centered design and the need for websites capable of rapid iteration.

Looking ahead, libraries are increasingly adopting tools such as Figma for wireframing, prototyping, and collaborative design (6). There is also growing recognition that UX work must extend beyond individual institutions. Resources like the UX in Libraries Conference (UXLibs), the peer-reviewed journal Weave, and professional interest groups within the American Library Association have created communities of practice that share knowledge and advance the field (8).

groups within the American Library Association have created communities of practice that share knowledge and advance the field (8).

User experience design has become integral to how libraries conceive and deliver their digital services. By placing users at the center of design decisions, employing research-based methodologies, and prioritizing accessibility, libraries are creating websites that better serve their diverse communities. The challenges are significant—from meeting evolving accessibility standards to balancing multiple user needs with limited resources—but the commitment within librarianship to user advocacy provides a strong foundation.

References

- ResearchGate. (2020, November 30). User Experience of Academic Library Websites. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347842976_User_Experience_of_Academic_Library_Websites

- Potter, N. (2024). User Experience (UX) in Libraries. https://www.ned-potter.com/ux-in-libraries-resource-list

- Naughton, R. (2023, February 15). Modern impressions: Understanding your library website users. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0099133323000149

- American Library Association. (2014). Applying user experience (UX) design to your library. https://www.ala.org/news/press-releases/2014/07/applying-user-experience-ux-design-your-library

- Bozkurt, A. (2024, November 18). UX / UI Design and Library Services. Medium. https://medium.com/@ayhanbzkrt/ux-ui-design-and-library-services-1348b3711efc

- Ex Libris Group. (2024, November 11). Library Management Systems: Enhancing UX for Better Design. https://exlibrisgroup.com/blog/when-ux-design-meets-the-library/

- UXpamagazine. (2017, May 7). The User Experience of Libraries: Serving The Common Good. https://uxpamagazine.org/the-user-experience-of-libraries/

- Yoon, K., Hulscher, L., & Dols, R. (2016). Accessibility and Diversity in Library and Information Science: Inclusive Information Architecture for Library Websites. The Library Quarterly, 86(2). https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/685399

- LibLime. (2024, April 4). Current Trends in Library Accessibility Technologies: Improving Access for All. https://liblime.com/2024/04/07/current-trends-in-library-accessibility-technologies-improving-access-for-all/

- Semple, N. (2023, January 29). Making Library Websites More Usable, Accessible, and Sustainable. https://nicolasemple.co.uk/2023/01/29/library-websites-usable-accessible-sustainable/

- ResearchGate. (2018, November 29). Evaluating the usability of the information architecture of academic library websites. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329294458_Evaluating_the_usability_of_the_information_architecture_of_academic_library_websites

- Choice 360. (2024, August 29). Ready for It? Ensuring Web Content Accessibility in Libraries. https://www.choice360.org/libtech-insight/ready-for-it-ensuring-web-content-accessibility-in-libraries/

- Taylor & Francis Online. Improving Library Accessibility Webpages with Secondary Feedback from Users with Disabilities. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19322909.2023.2246656