Library Cataloging Methods: An Analysis Of Current Standards And Their Merits

Library cataloging has undergone a significant transformation in recent decades, evolving from traditional card catalogs to sophisticated digital systems. While Machine Readable Cataloging (MARC) dominated from the 1960s through the early 2000s, the digital age has ushered in new methodologies designed to meet the complex needs of modern information retrieval (1). Today’s cataloging landscape features several competing and complementary approaches, each with distinct advantages and challenges. This article examines the primary cataloging methods currently in use, including Resource Description and Access (RDA), BIBFRAME, Dublin Core, and linked data approaches, analyzing their merits and applications in contemporary library settings.

Library cataloging has undergone a significant transformation in recent decades, evolving from traditional card catalogs to sophisticated digital systems. While Machine Readable Cataloging (MARC) dominated from the 1960s through the early 2000s, the digital age has ushered in new methodologies designed to meet the complex needs of modern information retrieval (1). Today’s cataloging landscape features several competing and complementary approaches, each with distinct advantages and challenges. This article examines the primary cataloging methods currently in use, including Resource Description and Access (RDA), BIBFRAME, Dublin Core, and linked data approaches, analyzing their merits and applications in contemporary library settings.

Resource Description and Access (RDA)

Resource Description and Access represents the most significant evolution in traditional cataloging standards since the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, Second Edition (AACR2). Initially released in 2010, RDA provides instructions for formulating bibliographic data and is intended for use by libraries, museums, and archives (2). The standard is based on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) and Functional Requirements for Authority Data (FRAD) models, which focus on user tasks and entity relationships (3).

Merits of RDA

One of RDA’s primary strengths is its user-centered approach. Unlike previous cataloging standards that emphasized the physical description of materials, RDA focuses on enabling better finding, identifying, selecting, obtaining, and exploring of information resources (4). This shift reflects a fundamental change in how libraries conceptualize their role in information discovery.

RDA also offers greater flexibility across different resource types and formats. The standard is media-neutral, meaning the same principles apply whether cataloging a physical book, an electronic journal, or a digital sound recording. This universality simplifies training and standardizes practice across diverse collections (3).

The Program for Cooperative Cataloging (PCC) has been implementing Official RDA through a rolling implementation from May 2024 to April 2027, demonstrating the standard’s continued relevance and evolution (5). This phased approach allows libraries to transition gradually while maintaining catalog integrity.

Challenges

Despite these advantages, RDA implementation has faced criticism. The standard’s complexity can overwhelm catalogers, particularly in smaller institutions with limited training resources. The RDA Toolkit, while comprehensive, requires subscription access, which can be cost-prohibitive for some libraries. Additionally, RDA records are still typically encoded in MARC format, which some critics argue perpetuates outdated data structures (1).

BIBFRAME and Linked Data

The Bibliographic Framework Initiative (BIBFRAME), initiated by the Library of Congress in 2011, represents a fundamental paradigm shift from traditional cataloging to linked data models (6). BIBFRAME is designed to replace MARC as the foundation for bibliographic description, grounding library data in linked data techniques and enabling better integration with the broader web (7).

The Linked Data Advantage

Linked data models focus on relationships rather than isolated records. Instead of describing materials solely through subject headings and authority records, linked data connects entities through URIs (Uniform Resource Identifiers). For example, a record for Mae Jemison might connect to data about NASA, African-American engineers, Cornell University, and Alabama, creating a rich web of discoverable relationships (8).

This approach offers transformative potential for library discovery. When a student researches Mae Jemison in a linked data-enabled catalog, the search could return not only materials directly about Jemison but also related resources about Alabama in the 1950s, African-American astronauts, or women in STEM fields—all from a single query (8). This contextual discovery mirrors how users interact with modern search engines.

This approach offers transformative potential for library discovery. When a student researches Mae Jemison in a linked data-enabled catalog, the search could return not only materials directly about Jemison but also related resources about Alabama in the 1950s, African-American astronauts, or women in STEM fields—all from a single query (8). This contextual discovery mirrors how users interact with modern search engines.

The benefits extend beyond individual library catalogs. By using standardized URIs and RDF (Resource Description Framework), libraries can connect their data to external databases like Wikipedia, VIAF (Virtual International Authority File), and national archives. This interoperability positions library resources to appear in general web search results, dramatically increasing their visibility (9).

Implementation Challenges

Despite its promise, BIBFRAME adoption has been gradual and contentious. As of 2023, primarily national libraries and large academic institutions—including the national libraries of Spain and Sweden, Stanford, Cornell, and the University of Concepción in Chile—have begun transitioning to BIBFRAME (10, 11). A few public libraries, including Denver Public Library, Dallas Public Library, Multnomah County Libraries, and San Francisco Public Library, have also started implementation (12).

Critics argue that libraries lack the resources to maintain the metadata infrastructure required for linked data. Kyle Banerjee contends tha t linked data is “more appropriate for limited domains that can be described using well-maintained vocabularies,” such as specialized research fields (13). Others suggest that the future lies in full-text indexing and artificial intelligence rather than linked data architectures (14).

t linked data is “more appropriate for limited domains that can be described using well-maintained vocabularies,” such as specialized research fields (13). Others suggest that the future lies in full-text indexing and artificial intelligence rather than linked data architectures (14).

Nevertheless, proponents maintain that despite current challenges, the advertised promises of linked data will materialize over time. Research from the National Library of Sweden, an early adopter, indicates strong belief in the long-term benefits even as libraries work through implementation obstacles (15).

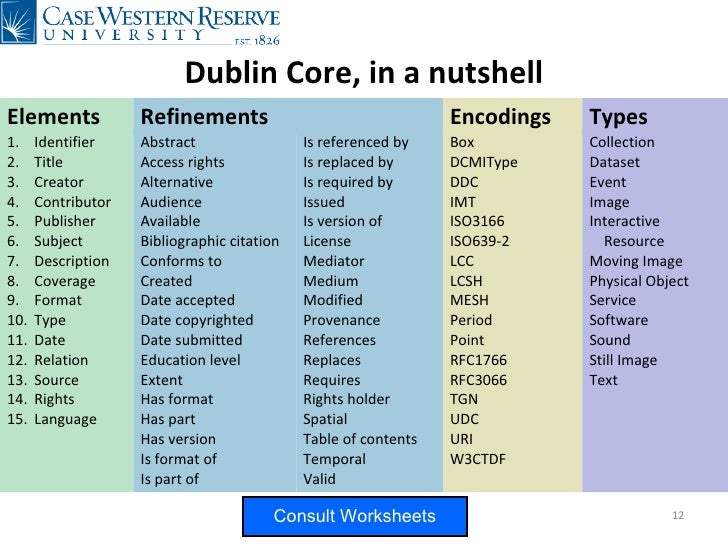

Dublin Core

The Dublin Core Metadata Element Set offers a simpler alternative to RDA and BIBFRAME. Developed initially to describe web resources in the 1990s, Dublin Core consists of 15 core metadata elements, including title, creator, subject, description, publisher, date, and format (16). The standard prioritizes simplicity and flexibility, with minimal constraints and optional elements.

Strengths of Dublin Core

Dublin Core’s primary merit is its accessibility. The standard requires minimal technical knowledge to implement and can be learned quickly, making it ideal for institutions with limited cataloging expertise or for describing diverse digital collections (17). Each element is straightforward and intuitive, reducing training time and implementation costs.

costs.

The standard’s flexibility allows it to accommodate various resource types without requiring complex encoding schemes. This adaptability has made Dublin Core popular for digital repositories, institutional archives, and special collections where complete MARC cataloging would be unnecessarily elaborate (18).

Dublin Core also supports interoperability. Many digital asset management systems and content management platforms have built-in support for Dublin Core, facilitating data exchange between systems. In 2008, Dublin Core was redefined as an RDF vocabulary, enabling integration with linked data initiatives while maintaining its essential simplicity (19).

Limitations

The very simplicity that makes Dublin Core attractive also limits its capacity for detailed description. The 15-element framework cannot capture the nuanced relationships and complex bibliographic data that RDA or BIBFRAME provide. This makes Dublin Core less suitable for comprehensive library catalogs that serve diverse research needs.

Additionally, the lack of controlled vocabularies in basic Dublin Core implementation can lead to inconsistency. Without authority control, different catalogers might describe the same resource differently, compromising discoverability. While qualified Dublin Core allows for more specificity, implementation then becomes more complex, potentially negating the original advantage of simplicity (20).

MARC: The Persistent Foundation

Despite discussions about its obsolescence, MARC remains the dominant encoding standard in libraries worldwide. Even RDA records are typically encoded in MARC format, and BIBFRAME implementations often begin with MARC-to-linked-data conversions. This persistence stems from MARC’s mature infrastructure, extensive training resources, and universal compatibility with integrated library systems.

However, MARC’s limitations in the web environment are well-documented. The format was designed for linear, print-based materials and struggles with complex digital resources. MARC’s hierarchical structure doesn’t naturally support the web’s networked, relationship-based information architecture. As cataloger Roy Tennant famously declared in 2002, “MARC must die” to allow libraries to participate in modern information ecosystems fully (21).

The transition away from MARC remains gradual, with many institutions maintaining hybrid approaches. URIs now appear throughout MARC records, creating a bridge between traditional cataloging and linked data futures (8). This evolutionary path allows libraries to preserve legacy data while moving toward more flexible frameworks.

Comparative Analysis

Each cataloging method serves different institutional needs and resource types. RDA works well for comprehensive research libraries requiring detailed bibliographic control across diverse formats. Its structured approach ensures consistency while accommodating modern resources, though at the cost of complexity and a learning curve.

BIBFRAME and linked data approaches offer the most forward-looking framework, positioning library data for optimal web integration and discovery. However, they require substantial technical infrastructure, staff expertise, and ongoing maintenance that many institutions struggle to provide. These methods are best suited for well-resourced institutions willing to invest in long-term transformation.

substantial technical infrastructure, staff expertise, and ongoing maintenance that many institutions struggle to provide. These methods are best suited for well-resourced institutions willing to invest in long-term transformation.

Dublin Core serves specialized needs—particularly digital collections, institutional repositories, and archives—where simplicity and rapid implementation outweigh the need for exhaustive description. It works best when integrated with other systems that provide additional context and structure.

Practical Considerations

Libraries choosing among these methods must consider multiple factors beyond theoretical merit. Budget constraints often determine whether institutions can afford RDA Toolkit subscriptions, BIBFRAME implementation projects, or staff training programs. Existing integrated library systems may limit options, as not all platforms support emerging standards.

Staffing expertise significantly impacts implementation success. Libraries with experienced catalogers can navigate RDA’s complexities and contribute to cooperative cataloging programs. Institutions with technology-savvy staff may pioneer linked data initiatives. Smaller libraries might prefer Dublin Core’s accessibility or continue with MARC-based workflows until vendor systems evolve.

Collection characteristics also matter. Noteworthy collections, digital repositories, and archival materials often benefit from flexible metadata schemes like Dublin Core. General circulating collections typically require the structure that RDA provides. Research libraries serving diverse scholarly needs may justify BIBFRAME investment to enhance discovery and interoperability.

Future Directions

The cataloging landscape continues evolving toward linked data models and enhanced web integration. Vendors are developing tools to convert MARC records to linked data ![]() formats and incorporating schema.org markup to make library resources discoverable through search engines (12). These efforts aim to increase library visibility while allowing institutions to transition gradually.

formats and incorporating schema.org markup to make library resources discoverable through search engines (12). These efforts aim to increase library visibility while allowing institutions to transition gradually.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning present both opportunities and uncertainties. Automated cataloging tools could reduce manual labor, though concerns about quality control and bias persist. Full-text indexing may eventually reduce reliance on traditional cataloging metadata, though this remains speculative.

No single cataloging method currently serves all library needs optimally. RDA provides robust standards for traditional bibliographic control while accommodating modern resources. BIBFRAME and linked data offer transformative potential for web-scale discovery but require substantial investment. Dublin Core delivers accessibility and flexibility for specialized applications. MARC persists as the working standard despite acknowledged limitations.

Libraries must evaluate their specific contexts—collections, users, budgets, and staff expertise—when selecting cataloging approaches. Many institutions adopt hybrid strategies, using different methods for different materials or implementing new standards gradually while maintaining legacy systems. As library professional Julia Unterstrasser observed regarding Sweden’s National Library, “while there are still many challenges and obstacles to tackle, there is a strong belief that the advertised promises of linked data will come true in time” (15).

The evolution of library cataloging reflects broader changes in how society creates, organizes, and discovers information. As technologies advance and user expectations shift, cataloging methods will continue adapting. The goal remains constant: connecting users with the information resources they need as efficiently and comprehensively as possible.

Sources

- Coyle, Karen. “The Evolving Catalog.” American Libraries Magazine, January 4, 2016. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2016/01/04/cataloging-evolves/

- “Resource Description and Access (RDA).” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/aba/rda/

- “Resource Description and Access (RDA).” Librarianship Studies, June 16, 2021. https://www.librarianshipstudies.com/2017/07/resource-description-and-access-rda.html

- “RDA Cataloging Resources.” New Mexico State Library. https://libguides.nmstatelibrary.org/rda

- “RDA Decisions, Policies, and Guidelines.” Library of Congress, Program for Cooperative Cataloging, updated August 28, 2024. https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/rda/PCC%20RDA%20guidelines/Post-RDA-Implementation-Guidelines.html

- Frank, Paul. “BIBFRAME: Why? What? Who?” Library of Congress, May 1, 2014. https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/bibframe/BIBFRAME%20paper%2020140501.docx

- “BIBFRAME – Bibliographic Framework Initiative.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/bibframe/

- “Transforming Library Catalogs: The Promise and Challenges of Linked Data.” Public Libraries Online, January 14, 2025. https://publiclibrariesonline.org/2025/01/transforming-library-catalogs-the-promise-and-challenges-of-linked-data/

- Mixter, Jeff. “Introduction to Library Linked Data.” OCLC Next Blog. https://blog.oclc.org/next/intro-to-library-linked-data/

- “BIBFRAME 2.0 Implementation Register.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/bibframe/implementation/register.html

- “BIBFRAME.” Wikipedia, October 2, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BIBFRAME

- “Linked Data.” Innovative Interfaces, Inc. https://polaris.iiidiscovery.com/?page_id=1203

- Banerjee, Kyle. “The Linked Data Myth.” Library Journal, August 13, 2020. https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/the-linked-data-myth

- Edmunds, Jeff. “BIBFRAME Must Die.” Penn State University Libraries, October 15, 2023. https://scholarsphere.psu.edu/resources/fc19faee-70b9-44b3-9346-18e40a2cd990

- Unterstrasser, Julia. “Linked Data and Libraries: How the Switch to Linked Data Has Affected Work Practices at the National Library of Sweden.” Uppsala Universitet, 2023. https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1773893&dswid=-4742

- “Dublin Core Metadata Schema.” University of California, Santa Cruz Library Guides. https://guides.library.ucsc.edu/c.php?g=618773&p=4306386

- “DCMI: Using Dublin Core.” Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. https://www.dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/usageguide/

- “METADATA AND DUBLIN CORE – Knowledge Organization and Processing – Cataloguing.” INFLIBNET. https://ebooks.inflibnet.ac.in/lisp3/chapter/metadata-and-dublin-core/

- “Dublin Core.” Wikipedia, June 19, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dublin_Core

- “Tutorial 3: Metadata Maker.” Dublin Core Metadata Initiative, September 1, 2023. https://www.dublincore.org/conferences/2023/sessions/tutorial-3/

- Tennant, Roy. “MARC Must Die.” Library Journal, October 15, 2002. https://soiscompsfall2007.pbworks.com/f/marc%20must%20die.pdf