The Impact of Personal Political Beliefs on Library Collection Management

Recently, I was reading library support group comments on social media and was amazed at how many librarians supported moving particular political biographies and autobiographies from their non-fiction area to fiction simply because the content or author of the books was objectionable to those librarians. Without going into which books they were discussing, it’s important to discuss how our personal biases can impact our professional decisions in collection management. Constructing and managing library collections is susceptible to the influence of individual political beliefs. There is a complex relationship between librarians’ political ideologies and the decisions they make in collection management, examining both the potential benefits and challenges this influence presents.

Understanding the Role of Collection Management

Collection management is a core function of libraries, involving the selection, acquisition, evaluation, and deselection of materials to meet the needs of the library’s community [1]. This process requires librarians to decide which materials to include or exclude, considering factors such as relevance, quality, demand, and budget constraints.

include or exclude, considering factors such as relevance, quality, demand, and budget constraints.

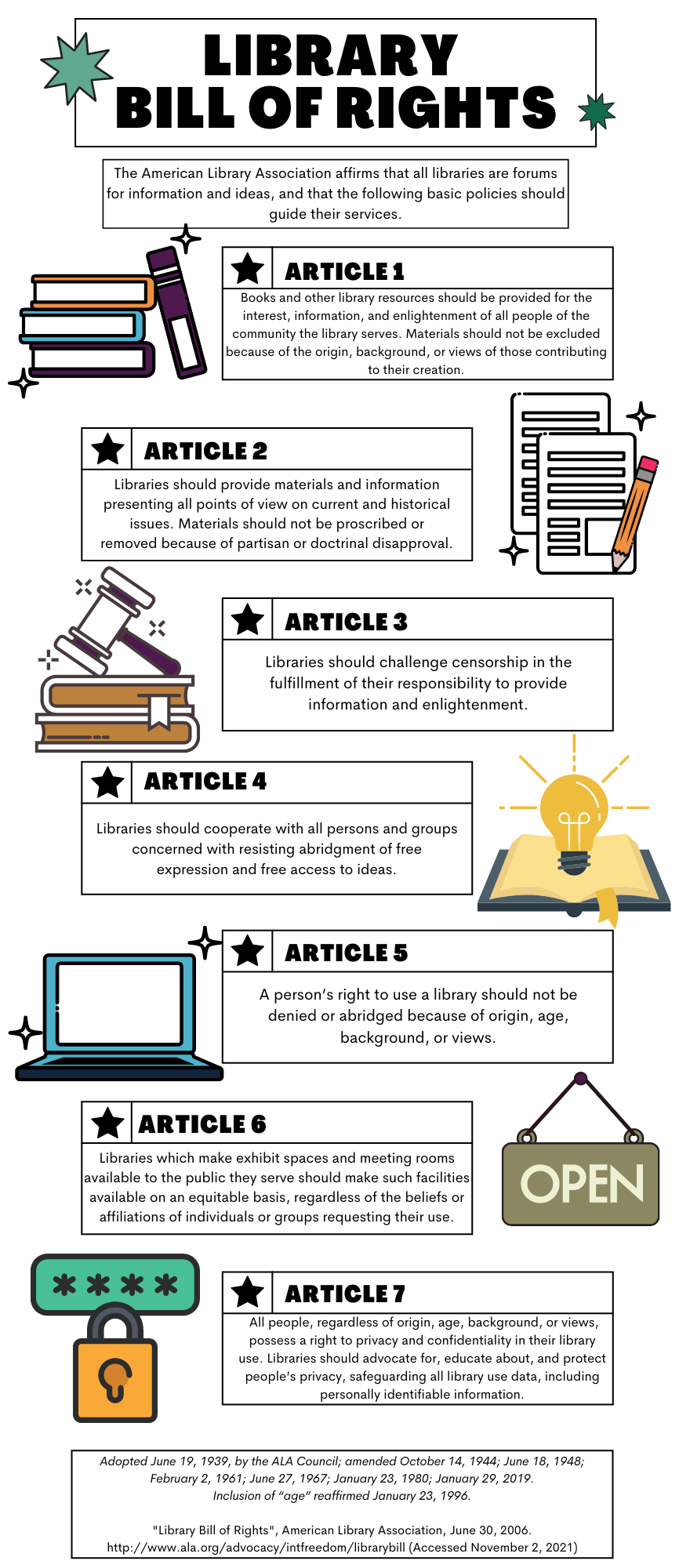

The American Library Association (ALA) emphasizes the importance of intellectual freedom and diversity in collection development. The Library Bill of Rights states, “Libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues” [2]. However, the practical application of these principles can be challenging, mainly when personal political beliefs come into play.

The Inevitable Influence of Personal Beliefs

Despite professional commitments to neutrality and objectivity, librarians, like all individuals, are shaped by their personal experiences, values, and political beliefs. These factors can unconsciously influence decision-making processes in collection management [3]. Recent studies have shown that librarians’ political leanings can affect various aspects of collection development, including:

- Selection Bias: Librarians may inadvertently favor

materials that align with their political views or unconsciously overlook those that challenge their beliefs [4].

- Interpretation of Community Needs: Personal political beliefs can influence how librarians interpret and prioritize the needs of their community, potentially leading to collections that reflect the librarian’s perspective rather than the community’s diverse views [5].

- Handling of Controversial Materials: Political beliefs may impact how librarians approach materials on controversial topics, affecting decisions about whether to acquire, where to shelve, or how to promote such items [6].

- Response to Challenges: When faced with challenges to materials in the collection, a librarian’s political beliefs may influence their willingness to defend certain items or their approach to the challenge process [7].

Case Studies and Research Findings

Several recent studies have shed light on the extent to which personal political beliefs can influence collection management:

In a 2023 survey of public librarians in the United States, researchers found a correlation between librarians’ self-reported political ideologies and their selection practices for materials on controversial topics such as climate change, gun control, and immigration [8]. The study revealed that librarians who identified as liberal were more likely to select materials presenting progressive viewpoints on these issues. In contrast, conservative-leaning librarians tended to favor materials with more traditional perspectives.

Another study conducted in academic libraries examined the impact of librarians’ political beliefs on the development of subject-specific collections [9]. The researchers found that in disciplines such as political science, sociology, and environmental studies, the political leanings of subject librarians were reflected in the balance of viewpoints represented in their collections.

A 2024 analysis of library collections in politically diverse communities revealed disparities in the representation of certain viewpoints based on the dominant political ideology of the area [10]. This study suggested local political climates could exert pressure on librarians, consciously or unconsciously influencing their collection decisions.

Potential Benefits of Political Diversity Among Librarians

While the influence of personal political beliefs on collection management presents challenges, it can also offer some benefits:

- Diverse Perspectives: A politically diverse library staff can bring a broader range of viewpoints to the development

process, potentially resulting in more balanced and comprehensive collections [11].

process, potentially resulting in more balanced and comprehensive collections [11].

- Representation of Minority Views: Librarians with non-mainstream political beliefs may be more attuned to the need to represent minority viewpoints in the collection, ensuring that underrepresented perspectives are included [12].

- Critical Evaluation: Diverse political beliefs among staff can foster more rigorous debates and critical evaluation of materials during the selection process [13].

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

The influence of personal political beliefs on collection management also raises several challenges and ethical considerations:

- Balancing Personal Views with Professional Responsibility: Librarians must navigate the tension between their beliefs and their professional obligation to provide balanced, diverse collections [14].

- Transparency and Accountability: There is a need for greater transparency in the collection development process to ensure that personal biases are not unduly influencing decisions [15].

- Intellectual Freedom vs. Community Standards: Librarians must balance intellectual freedom with respecting community standards and values, which can be particularly challenging when personal political beliefs align with one side of this debate [16].

- Self-Awareness and Bias Recognition: Developing the self-awareness to recognize and mitigate one’s biases is an ongoing challenge for librarians engaged in collection management [17].

Strategies for Mitigating Bias in Collection Management

To address the potential negative impacts of personal political beliefs on collection management, libraries and librarians can employ several strategies:

- Diverse Collection Development Teams: Forming collection development teams with diverse political viewpoints can help balance individual biases and ensure a range of perspectives in the selection process [18].

-

Structured Selection Criteria: Implementing clear, objective selection criteria can help minimize the influence of personal beliefs on collection decisions [19].

Structured Selection Criteria: Implementing clear, objective selection criteria can help minimize the influence of personal beliefs on collection decisions [19].

- Regular Collection Audits: Conducting regular audits of the collection to assess balance and diversity can help identify areas where personal biases may have influenced selection [20].

- Professional Development: Offering training on recognizing and mitigating personal biases can help librarians become more aware of how their beliefs may influence their work [21].

- Community Engagement: Actively seeking input from the community on collection development can help ensure that the collection reflects the diverse needs and viewpoints of library users rather than the personal beliefs of librarians [22].

- Collaborative Collection Development: Participating in consortia or collaborative collection development initiatives can help balance individual biases by distributing decision-making across multiple institutions [23].

The Future of Collection Management in a Politically Polarized World

As political polarization continues to increase in many societies, the challenge of managing personal political beliefs in collection development is likely to become more pronounced. Future trends and considerations may include:

- AI-Assisted Selection: Developing AI tools for collection management may help reduce human bias. However,

careful implementation is necessary to avoid perpetuating algorithm biases [24].

- Increased Scrutiny: Libraries may face greater public scrutiny of their collections, requiring more transparent processes and justifications for selection decisions [25].

- Emphasis on Information Literacy: As the line between fact and opinion becomes increasingly blurred in the digital age, libraries may need to focus more on developing users’ information literacy skills to navigate diverse and sometimes conflicting viewpoints [26].

- Evolving Professional Ethics: The library profession may need to evolve its ethical guidelines to more explicitly address the role of personal political beliefs in collection management [27].

The influence of personal political beliefs on library collection management is a complex and nuanced issue. While it challenges the principles of neutrality and balanced representation, it also reflects the human element inherent in the curatorial process of building library collections.

The key lies in finding a balance between acknowledging the inevitability of some degree of personal influence and implementing strategies to mitigate its potential negative impacts. By fostering self-awareness, promoting diversity within the profession, and maintaining a commitment to intellectual freedom and community needs, libraries can continue to build collections that reflect a wide range of perspectives and serve as vital resources for information and ideas in our complex world.

Sources:

[1] Horava, T. (2010). Challenges and possibilities for collection management in a digital age. Library Resources & Technical Services, 54(3), 142-152.

[2] American Library Association. (2024). “Library Bill of Rights.” ALA Website.

[3] Quinn, B. (2012). Collection Development and the Psychology of Bias. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 82(3), 277–304. https://doi.org/10.1086/665933

[4] “Strategic Planning in Academic Libraries: A Political Perspective”, American Library Association, September 29, 2006

https://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/booksanddigitalresources/booksmonographs/pil/pil49/birdsall

[5] Hodges, A. (2014, May 20). The practical librarian’s guide to collection development. American Libraries Magazine. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2014/05/20/the-practical-librarians-guide-to-collection-development/

[6] “Policies on Selecting Materials on Controversial Topics,” American Library Association, December 25, 2017

https://www.ala.org/tools/challengesupport/selectionpolicytoolkit/controversial

[7] Resources for Book Challenges. https://www.ala.org/aasl/about/challenges

[8] Jahnke, L., Tanaka, K., & Palazzolo, C. (2022). Ideology, Policy, and Practice: Structural Barriers to Collections Diversity in Research and College Libraries. College & Research Libraries, 83(2), 166. doi:https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.83.2.166

[9] Rashid, M. H. A. (2024, March 1). How to identify and address bias in library collection development. Libraries in the Middle. https://limbd.org/how-to-identify-and-address-bias-in-library-collection-development/

[10] Levenson, H. N., & Hess, A. N. (2020). Collaborative collection development: Current perspectives leading to future initiatives. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(5), Article 102201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102201

[11] Carmack, N. (2021). Collecting for diversity, equity, and inclusion: Best practices for Virginia libraries. Virginia Libraries, 65(1), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.21061/valib.v65i1.622.

[12] Kumaran, M. (2020, November 30). Beyond tokenism: The importance of staff diversity in libraries. BCLA Perspectives. https://bclaconnect.ca/perspectives/2020/11/30/beyond-tokenism-the-importance-of-staff-diversity-in-libraries/

[13] Halevi, G. (2024, March 22). Biblio-equity in action: Advancing collection development for diversity, equity, and inclusion. CLOCKSS. https://clockss.org/biblio-equity-in-action-advancing-collection-development-for-diversity-equity-and-inclusion/

[14] Luo, L. (n.d.). Ethical issues in reference: An in-depth view from the librarians’ perspective. San Jose State University, School of Information. https://journals.ala.org/index.php/rusq/article/view/5928/7515

[15] International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. (2019). Guidelines for collection development policies for libraries: An IFLA professional report. https://www.ifla.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/assets/acquisition-collection-development/publications/gcdp-en.pdf

[16] Macdonald, S. (2023). Intellectual freedom and social responsibility in library and information science: A reconciliation. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006231160795

[17] American Library Association. (n.d.). Keeping up with bias. Association of College & Research Libraries. https://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/keeping_up_with/bias

[18] Levenson, H. N., & Nichols Hess, A. (2020). Collaborative collection development: current perspectives leading to future initiatives. Journal of academic librarianship, 46(5), 102201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102201

[19] American Libraries. (2021, January 4). Mitigating implicit bias. American Libraries Magazine. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2021/01/04/mitigating-implicit-bias/

[20] Walters, W. (2023). Assessing Diversity in Academic Library Book Collections: Diversity Audit Principles and Methods. Open Information Science, 7(1), 20220148. https://doi.org/10.1515/opis-2022-0148

[21] Gino, F., & Coffman, K. (2021, September-October). Unconscious bias training that works: Increasing awareness isn’t enough. Teach people to manage their biases, change their behavior, and track their progress. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/09/unconscious-bias-training-that-works

[22] Boudewyns, D. K., & Klug, S. L. (2014). Collection Development Strategies for Community Engagement. Collection Management, 39(2–3), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2014.890994

[23] Pan, D., & Fong, Y. S. (2010). Return on investment for collaborative collection development: A cost-benefit evaluation of consortia purchasing. Collaborative Librarianship, 2(4), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.29087/2010.2.4.06

[24] Raykar, D. S., & Sontakke, S. N. (2023). The use of artificial intelligence in library management. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR), 10(6), h122. https://www.jetir.org/view?paper=JETIR2306715

[25] Scott, D., & Saunders, L. (2021). Neutrality in public libraries: How are we defining one of our core values? Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 53(1), 153-166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000620935501

[26] Gaultney, I. B., Sherron, T., & Boden, C. (2022). Political polarization, misinformation, and media literacy. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 14(1), 59-81. https://doi.org/10.23860/JMLE-2022-14-1-5

[27] Ethical considerations in data collection and analysis: A review: Investigating ethical practices and challenges in modern data collection and analysis. (2024). International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, 6(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijarss.v6i1.688