Open and Accessible

The need for self-archiving and sharing those files with colleagues quickly brought about “The first free scientific online archive…arXiv.org, started in 1991, initially a preprint service for physicists, initiated by Paul Ginsparg” (Liquisearch.com). The end of the 20th century and the dawn of the 21st brought even more rapid changes to the information landscape. Digital archives in various forms for specific purposes (medical, health, history) were the most common OA available. One of the first primary OA tools still used by millions today was created in 1997. “The U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM) made Medline, the most comprehensive index to medical literature on the planet, freely available in the form of PubMed. Database usage increased tenfold when it became free, suggesting that prior limits on usage were impacted by lack of access…” Following this, in 2001, after the success of BioMed Central, PLoS was created with a 10 million dollar grant as an alternative to subscription platforms. “…34,000 scholars around the world signed “An Open Letter to Scientific Publishers”, calling for “the establishment of an online public library that would provide the full contents of the published record of research and scholarly discourse in medicine and the life sciences in a freely accessible, fully searchable, interlinked form”. Scientists signing the letter also pledged not to publish in or peer-review for non-open access journals. This led to the establishment of the Public Library of Science, an advocacy organization” Liquisearch.com. From there, OA has only evolved and become more open and accessible. With this evolution, a few types of OA came into existence.

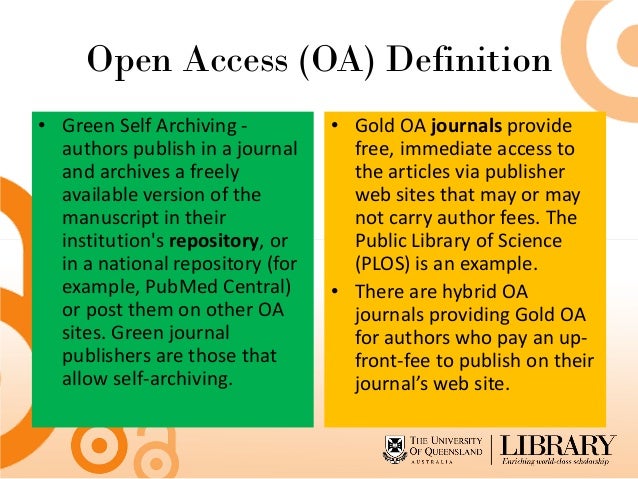

Gratis vs. Libre OA are similar in that they both make information freely available to anyone. However, Gratis OA doesn’t allow the information to be “the right to make copies, distribute, or modify the work in any way beyond fair use.” Libre makes content “With a Creative Commons license, researchers can “give the public permission to share and use [their] creative work” on a legal basis.” There are also Green vs. Gold types of publishing routes. “…The first “involves archiving a version of the manuscript in an [open access] repository,” such as a public archive, while the second “involves publishing articles or books . . . on a publisher’s platform.” The gold route comes at a cost but has several advantages, including the prestige associated with being published by a well-known scholarly journal.” Once the choice is made of which type of OA to use, from there other researchers and students can access the information.

SPARC (The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition) “presents a convincing argument on the need for open access. Although much research is government funded, with researchers and peer reviewers receiving little to no compensation for their work, the benefits of research are limited by paywalls. SPARC points out the underlying contradiction in the current publication model: “though research is produced as a public good, it isn’t available to the public who paid for it.” The results of potentially groundbreaking research “are hidden behind technical, legal, and financial barriers.” Open access breaks down these barriers, with potentially dramatic outcomes.” Thinking of how much more could be discovered, learned, applied, and shared due to OA being more standard. Researchers would have more resources to choose from, and libraries could devote more of their serial’s budget to other matters.

By Gretchen Hendrick Gardella, MLIS

Gretchen Hendrick Gardella is a Librarian with administrative, research, and vast technical skills. Ms. Gardella brings over 16 years of experience working in academic and public libraries to the discussion.